Overview

States rely on data from the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) to identify and monitor troubling trends in adolescent health and develop programmatic and policy interventions. In January, YRBSS data were among many federal data resources pulled from public access in response to vague and scientifically unsupported executive orders signed by President Trump. The result is a dangerous blind spot at precisely the moment when schools, health agencies, and policymakers need clear information the most.

Across the country, communities are grappling with a sharp rise in youth mental health challenges, self-harm, suicide, and bullying. In the decade leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, persistent sadness, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation among teens rose by about 40 percent. The pandemic deepened the crisis—intensifying social isolation, disrupting academic and social lives, and compounding housing and food insecurity.

Although CDC data from 2021 to 2023 showed modest improvements—such as a decrease from 42 to 40 in the percentage of students who experienced persistent feelings of hopelessness or sadness—teen mental health statistics remain significantly worse than just a decade ago. Significant disparities also persist, particularly among female and LBGTQ+ teens. Equipped with knowledge about the scope and nature of the mental and behavioral health problems afflicting our youth, policymakers, schools, health care providers, and parents can take effective action to support kids.

These challenges remain urgent, but the data we rely on to understand them—and to respond effectively—is starting to disappear.

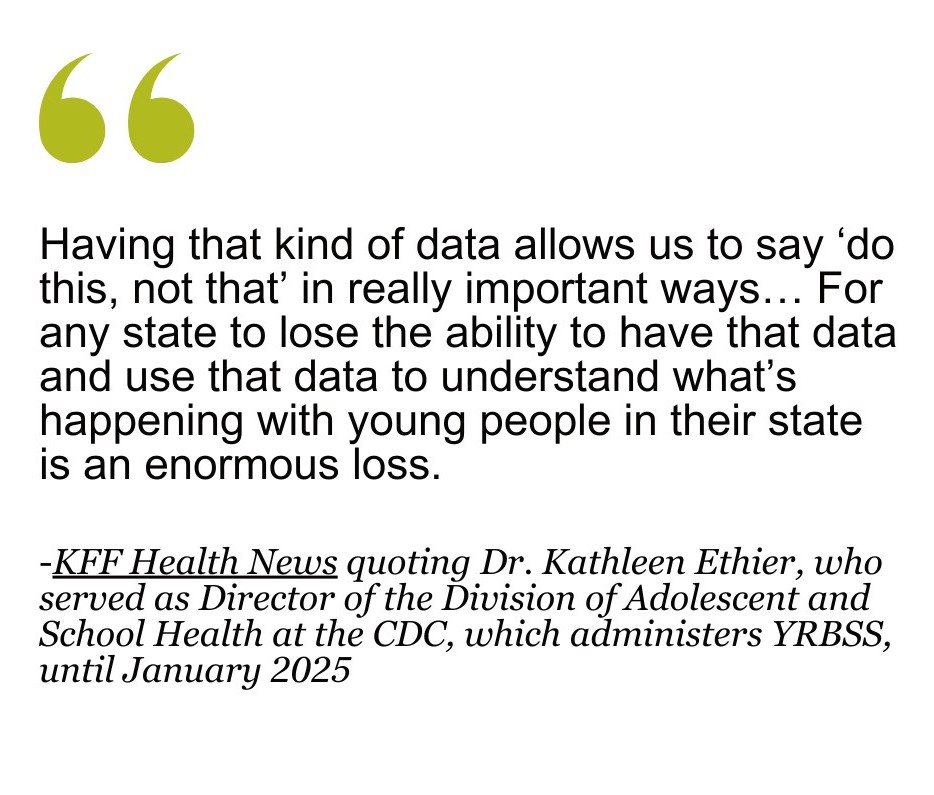

For more than three decades, the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS) has served as a cornerstone of tracking the leading causes of death and injury among young people. An anonymous nationwide survey with state and local components, YRBSS data are released every two years, providing essential insights into students’ experiences with depression, alcohol and drug use, bullying, sexual health, diet, physical activity, sleep, and more, informing everything from state public health and education funding decisions to local prevention programs.

States rely on YRBSS data to identify and monitor troubling trends in adolescent health and develop programmatic and policy interventions. For example, Utah’s Department of Health leveraged its YRBSS findings to develop its SafeUT mobile app and Live On suicide prevention campaign, which was established by legislation in 2019 and launched in 2020. While suicide is still the leading cause of death for young Utahns aged 10-24, the state saw a decrease in deaths due to intentional self-harm for teens aged 15-19 from 2017 to 2022.

Connecticut secured approval to add its own question about disability to the state-specific portion of YRBSS and as a result, learned that students with Individualized Education Program plans (IEPs) were more likely to be bullied and cyberbullied and to use drugs. This demographic-specific data can drive programming and supports.

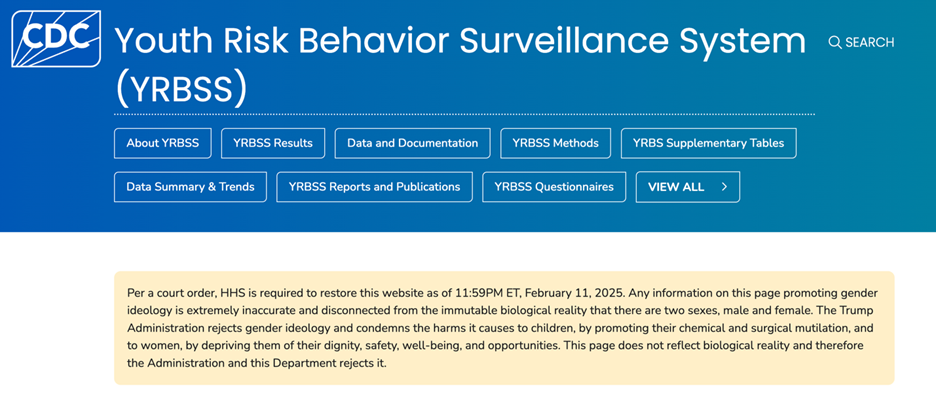

On January 31, 2025, YRBSS data were among many federal data resources pulled from public access in response to vague and scientifically unsupported executive orders signed by President Trump related to terminating “gender ideology” and diversity, equity, and inclusion data, research, policies, and communications. State and local governments, which depend on federal data for many vital functions from disaster response to urban planning, have been left stymied.

On February 11, 2025, a federal court ordered CDC and other agencies “to restore to their versions as of January 30, 2025” of datasets and webpages that had been removed from public access “without adequate notice or reasoned explanation.” A visit to the YRBSS website as of this writing shows a banner across the top that alleges that data developed over decades of research is “extremely inaccurate” and, in an unprecedented move, articulates a scientific opinion by a sitting president that is overly simplistic and unsupported by most of the scientific community.

It appears that YRBSS will continue to allow states to customize the state-specific survey, including adding questions related to gender identity. While critical to monitoring areas of youth health that are no longer covered nationally, cross-state and national comparisons will not be possible, and disparities for LBGTQ+ youth and other populations at risk will persist or worsen in states that follow the Administration’s lead.

The deletion of critical public health data is just one part of a seemingly irrational assault on the federal scientific systems upon which researchers and state public health officials rely to monitor and respond to Americans’ health.

Just this week, lawyers for CDC director Dr. Susan Monarez argued that her dismissal was “legally deficient” and symptomatic of a much larger problem—the silencing and politicization of science, noting that “[i]t is about the systematic dismantling of public health institutions, the silencing of experts, and the dangerous politicization of science. The attack on Dr. Monarez is a warning to every American: Our evidence-based systems are being undermined from within.” In a May 2025 Science article, the authors argue that, “Federally supported science has been so successful, in no small part, because agency staff are typically expert scientists beholden to ensuring that the agencies deliver world-class science,” but that agencies “cannot meet their statutorily mandated scientific missions if politics, rather than scientific expertise, drive decision-making.”

Some states have sought to stand in the gap by ramping up behavioral health screenings and seeking non-federal partners to address the youth mental health crisis. In July 2025, Illinois passed a law requiring annual mental health screenings for all students grades 3-12 beginning in 2027. Six states – Alabama, Hawaii, Kentucky, New Jersey, Oklahoma and Virginia – participated in a National Governors Association program to receive technical assistance and support to advance targeted reforms to their state youth mental health systems. Eleven states—Colorado, Michigan, Minnesota, California, Iowa, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Virginia, and Utah—participated in an AmeriCorps grant program to train and recruit mental health peer support specialists and navigators in schools.

Still other states have compounded the effects of federal restrictions by withdrawing from the YRBSS (a few even before federal restrictions), passing laws that require active parental consent for student participation in school-based surveys, or instituting their own untested state youth risk surveys. (The Network has published a fact sheet outlining state laws that require active—as opposed to “opt out”—parental consent for school-based surveys. Since 1974, federal law has required parental notice and the opportunity to opt-out of any school-based survey that involves certain “protected areas,” including mental health and sexual behavior.)

Furthermore, the scientific rigor of new state surveys is uncertain. For example, Florida withdrew from the YRBSS in 2022 without legislative action or justification. While the YRBSS was developed and maintained over the course of several years with strict safeguards to ensure validity and reliability, according to the Florida Policy Institute, the Florida-Specific Youth Survey was developed and administered in just six months without public transparency.

Federal and state restrictions on public health data jeopardize data quality, continuity, and comparability across time and jurisdictions, resulting in missed warning signs, ineffective interventions, and preventable harm. The result is a dangerous blind spot at precisely the moment when schools, health agencies, and policymakers need clear information the most. Publicly funded, congressionally authorized health surveillance systems must be restored and protected in ways that uphold scientific rigor and consensus, even when that consensus challenges political and ideological agendas. When politics erase data and silence science, it’s not just the numbers we lose—it’s the ability to safeguard the mental health, safety, and futures of young people who are depending on us to see them clearly.

This post was written by Kerri McGowan Lowrey, J.D., M.P.H., Deputy Director, Network for Public Health Law—Eastern Region.

The Network promotes public health and health equity through non-partisan educational resources and technical assistance. These materials provided are provided solely for educational purposes and do not constitute legal advice. The Network’s provision of these materials does not create an attorney-client relationship with you or any other person and is subject to the Network’s Disclaimer.

Support for the Network is provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF). The views expressed in this post do not represent the views of (and should not be attributed to) RWJF.